“The rise of the machine”: High frequency trading and food prices

A rough consensus has emerged around the causes of the high food prices that spiraled up in 2007 and 2008; increasing global food demand due to rising incomes and population, stalling agriculture productivity, and biofuels. But one factor that remains hotly debated is the role of financial speculation in food prices. The amount of food […]

A rough consensus has emerged around the causes of the high food prices that spiraled up in 2007 and 2008; increasing global food demand due to rising incomes and population, stalling agriculture productivity, and biofuels. But one factor that remains hotly debated is the role of financial speculation in food prices.

The amount of food produced and consumed has grown gradually in the last decade, but the amount of investment interest in food commodities has skyrocketed. For the most part, investors and speculators are not actually buying food commodities; they are buying futures contracts and various financial derivatives. Volumes have grown from less than $10 billion to more than $450 billion in a little over a decade. And while commodities markets once were largely composed of speculators who were directly engaged in food industries, financial investors—index funds, hedge funds, etc.—now dominate the markets. The usual explanation of the rapid movement of capital into commodities is that investors were seeking new, safer places to put money now that economic catastrophes have struck dot-coms, the stock market, the housing sector, and even government debt. Commodities, historically, have not been as tied to other economic assets, so are a good hedge; i.e. if the stock market collapses, commodities might not—and vice-versa.

Some analysts argue that this investor rush into commodities has inflated food prices. But the dominant view is that this financial activity on futures contracts and derivatives doesn’t really affect prices directly—that “market fundamentals” of supply and demand are still what determines the price of corn on Chicago Mercantile Exchange.

Part of the challenge is finding a way to test the question. The accelerating financial activity is not in physical hording or dumping of agriculture commodities, but in trading futures contracts and “derivatives” of these contracts—some of them quite exotic, obscure, or unregulated. The analytical tools to measure the impact of speculative activity on prices are not well developed. Attempts to do this have usually found no impact—or found mixed results. But it’s also true that the methods have been flawed—only able to capture parts of the market and activity—and good data is not always available.

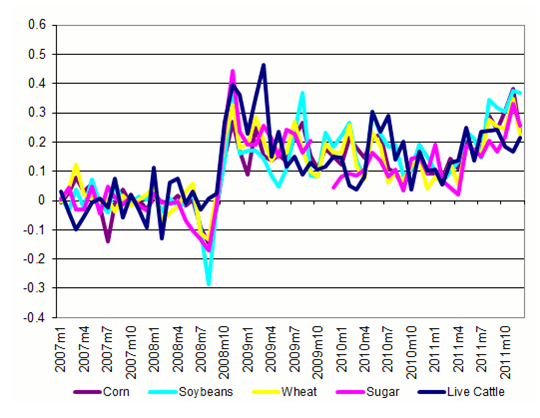

Now comes a contribution from researchers at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). They tried to investigate commodities trading at shorter intervals than the standard daily rate (i.e. were prices up or down each day?). Instead, they look at data measuring trades at one second, 10 seconds, 5 minutes, and one-hour. They analysis tells an interesting story, shown in this graph (Source: VoxEU.org):

What it measures is the correlation between commodities futures prices and stock market futures. And what it shows is that starting in 2008, at the height of the food price crisis—and at the moment of the collapse of Lehman Brothers, something changed. Before then, commodities futures and stock market futures had low correlation; close to zero. After that point, they have begun to move together more closely; closer to 1, which would be perfect correlation.

So, what does this tell us?

Well, I’m not totally sure. And this is just one study. And, you could certainly ask whether this tool—measuring the correlation of short-term movements between commodities futures and equities futures—is useful.

But here are some possible implications:

The authors say that “high-frequency trading strategies, in particular the trend-following ones, are playing a key role.” They argue that the “financialization” of commodity markets is impacting price determination—that if prices were set based on supply/demand fundamentals, there shouldn’t be a correlation with equities. Commodity prices should be affected by seasons, weather, demand, etc. not by changes in stock market prices. They find similar correlations over a range of commodities—including non-food commodities. So—they argue—the shifting “financialization” is changing price formation.

They argue that linking commodity markets to financial actors and stock markets in this way means “commodity markets are more and more prone to events in global financial markets and more likely to deviate from their fundamentals.”

The linkage also undermines the purpose of many financial actors in investing in commodities; to hedge against other markets, like the stock market. The idea that they are increasingly correlated will mean that commodities won’t be safe if the stock market crashes.

If true—and if, indeed, caused by the high frequency trading—this might also add the arguments in favor of measures like the financial transaction tax, which could help to mediate or reduce this linkage and risk.