Farm Bill cliff: A more trade-distorting farm policy

The insular logic of the Farm Bill means farmers in other countries pay a price.

Every now and then, I get a call from a colleague in Geneva, asking me about the Farm Bill. Although colleagues in Geneva often find Farm Bill politics confusing, they are quite interested in Farm Bill policy. That’s because US agriculture policy is, effectively, trade policy, since the USA is such a large exporter of agriculture products. And Geneva is the global capital of trade policy, home to the World Trade Organization.

A useful analysis of the next Farm Bill comes from the Geneva-based ICTSD. The authors question whether the new Farm Bill will distort trade more or less than the old one. To do this, they dig through the House and Senate versions of the Farm Bill and try to understand the dazzling complexity of both the existing and new proposed farm programs. Of course, the new Farm Bill is not a finished product, and the House of Representatives has not even passed a bill yet. But the authors do their best.

Central to the new Farm Bill policy is eliminating “direct payments” and using the savings to create or enhance a variety of price and revenue guarantees. Direct payments don’t vary at all based on behavior, weather or prices—they are just automatic payments to farmers. Trade purists like direct payments because they don’t influence farmers’ planting decisions (because they are paid no matter what) and don’t distort trade. But everyone else hates them because they seem like a ridiculous government payout to farmers for doing almost nothing.

The paper concludes that:

“The overall thrust of the new farm bill is that decoupled direct payments that have minimal impact on planting decisions will be replaced by coupled safety net programs that potentially have a large impact on planting decisions.”

The authors project the impact of the new Farm Bill programs, and find rather modest changes; this is because current high crop prices mean government subsidy programs don’t have to pay out. But if prices decline in the future, the new Farm Bill could be more expensive to taxpayers and more influential on farmer’s business decisions.

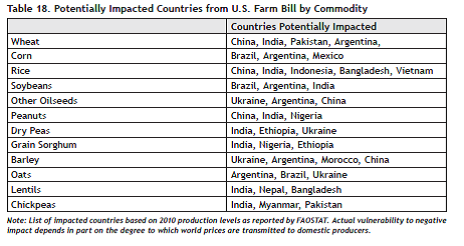

The paper argues that the new Farm Bill will be more likely to distort trade and harm foreign producers of agriculture products than the status quo. The authors do us a favor and identify which countries’ farmers might be most bothered by the new Farm Bill:

The new Farm Bill will shift the balance of support among commodities. The study finds that projected subsidies for cotton are about three times higher than for other commodities, which could induce farmers to shift to cotton from other crops—something Brazil is likely to be unhappy about. And rice producers get a pretty sweet deal in the new Farm Bill, which could induce farmers to produce more rice, something Haitian rice producers might not be excited about.

Why are cotton and rice winning the Farm Bill? Two maps tell the story.

This map shows where different commodities are grown—notice cotton and rice in orange and black:

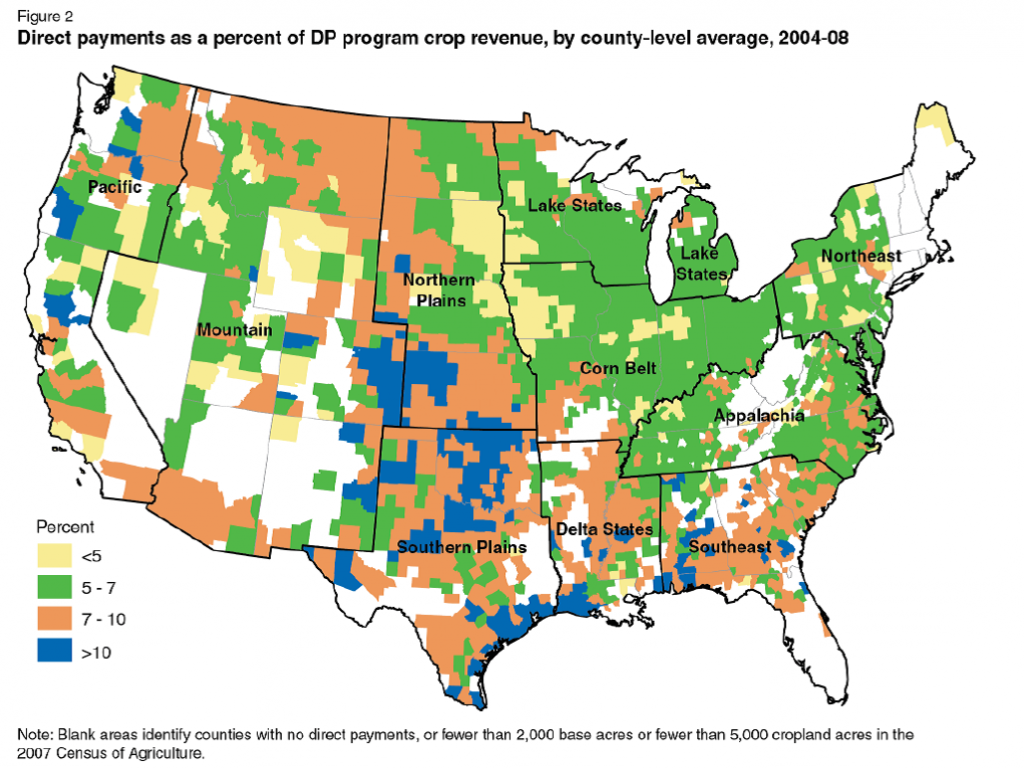

And this map shows where farmers are more dependent on government direct payments for their crops in blue and orange :

You can see a rough correlation between farmers who depend more on government direct payments (first map) and areas where cotton and rice (and peanuts) are grown (second map).

In the insular and circular logic of the Farm Bill, commodities that lose subsidies in one area demand—and expect—those subsidies to be made up somewhere else. Since direct payments are being eliminated, the lobbyists for cotton, rice and peanuts have pushed hard—and successfully—for a bigger share of the new Farm Bill subsidies.

But more trade-distorting subsidies for cotton and rice and peanuts is the wrong direction for US farm policy. A better farm policy would be supporting a robust, diverse, and resilient agriculture that is more flexible, less tied to government policy. We need farmers to respond to changing markets and changing weather, rather than Farm Bill dictates. They should invest in creative farming rather than lobbyists. Rigging subsidies and markets only makes the system more rigid, more vulnerable to corruption, to disaster, to bad behavior. Government policy should not be picking one crop over another, one sort of farmer over another.