Pulling back the corporate tax curtain: Why new US tax rules could matter for you

U.S. Treasury building, Washington, DC. Source: Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Treasury building, Washington, DC. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The announcement of new US Treasury rules for multinational corporations this week could have a significant impact on American taxpayers and citizens of developing countries alike.

The Internal Revenue Service recently held a public hearing that I attended with my fellow partners from the Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency (FACT) Coalition to offer comments on proposed US Treasury rules for enhancing the transparency of US multinational corporations (MNCs).

While it may not sound exciting to some, the implications of these rules – depending on what they include – could be significant. And not just for corporations, but for Americans and citizens of developing countries alike.

The rules would require US multinational corporations to file a country-by-country report (CBCR) which means they would publish information regarding income and taxes paid for all jurisdictions in which they operate as part of their financial statements. This concept was prompted by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and G20’s “Base Erosion and Profit Shifting” (BEPS) project, which aimed to curb “aggressive tax planning” strategies. Through these strategies, MNCs exploit gaps and mismatches in tax rules to artificially (though nonetheless legally) shift their profits to low- or no-tax jurisdictions and therefore pay little to no corporate taxes – a.k.a. tax dodging.

The 2013 BEPS Action Plan resulted in a list of 15 actions, the 13th of which recognizes the importance of access to a multinational company’s tax information for countries – especially in developing countries – so they can better assess and address the tax revenue lost because of the aggressive tax avoidance practices of MNCs operating within their borders.

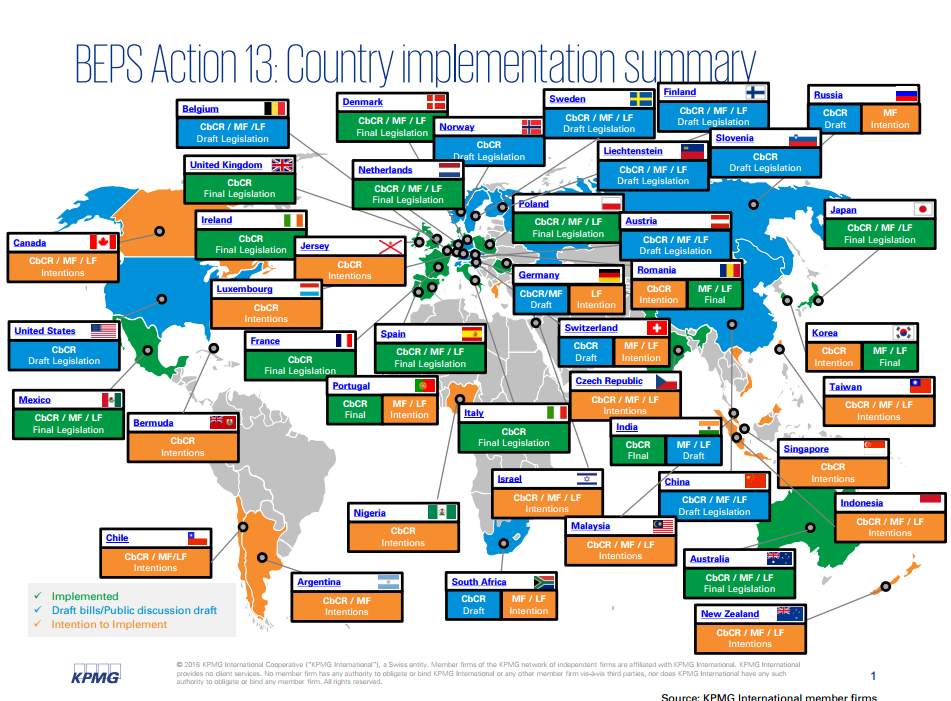

Since the adoption of the action plan, several developed nations have begun to change their tax systems in response to Action 13. As the home of the largest number of major multinationals in the world, it is certainly time that the U.S. joins in the effort.

What’s in it for US taxpayers?

One might wonder how this kind of corporate reporting regulation would make any difference for US tax payers and citizens of other countries where US companies operate. Economist Kimberly Clausing of Reed College recently estimated that profit-shifting by MNCs is likely to cost the US government approximately $94 billion to $135 billion in corporate tax revenue by 2016. These practices erode the US tax base, which in practical terms amounts to lower federal and state budgets, increased deficits, disadvantages for small businesses, and less money available for critical social services like education, roads and health care. Corporate tax dodging also means that the government will have to disproportionately rely on more tax from less well-off taxpayers to make up for the multi-billion dollar void created by corporate tax dodging.

On a global level, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development estimated that the same practices from MNCs lead to a loss of $100 billion every year for developing countries around the world. Profit-shifting drains money out of developing countries, undercutting US foreign aid investments, increasing poverty, and contributing to economic instability. The damage done to American citizens as well as citizens of poor countries by these corporate tax practices are two sides of the same coin as pointed out earlier this year in Oxfam’s Broken at the Top report.

A truly global movement?

It’s a no brainer that a robust global movement is required to stop corporate tax dodging and reduce the harm done to citizens in developed and developing countries alike. At an individual level, it is difficult for a single country to adopt tough rules against global companies who threaten to relocate jobs and investments at the mention of any single tax change. However, when countries move together to close gaps, the playing field can become more level and countries can prevent companies from playing one jurisdiction against another in a devastating race to the bottom.

That is why we need to increase consensus and coordination amongst northern and southern countries on transparency efforts, and tighten anti-avoidance rules in order for country-by-country reporting to be successful and to avoid even greater revenue losses.

Some countries, including top US trading partners, have already taken steps either by submitting or approving bills implementing country-by-country reporting. As per the timeline recommended by the OECD, all countries moving forward on implementing the reporting requirements were expected to have them in force on or after January 1 of this year.

Where does the US stand in this process?

Even though the US has not been an early implementer, the country can still benefit from the leveling effect of this global effort by passing a robust set of final Treasury rules (due to be released June 30) for country-by-country reporting.

Today, countries cannot access reliable country-specific information on where large US multinationals operate, how many employees they have, the size of their capital investments, the amount of their profits or losses, or the taxes they pay. Considering that the US alone houses more than 20 percent of the world’s largest public multinational companies, access to this information will significantly impact global efforts for improved corporate tax transparency. The information to be collected in country-by-country reporting by US companies will for the first time provide accurate and timely economic, business, and tax information that could play an invaluable role in designing effective and efficient US policy.

It is unlikely that we will get country-by-country reporting for all countries overnight, but this kind of transparency is possible. It has nearly been reached in the extractive industries sector. Seeing the global mobilization that has been created around transparency in extractive industries, I suspect we will have it for all sectors in less than ten years.

Based on the disproportionate amount of US-based multinational corporations in the world, it is certain that the US must take part in global transparency efforts for maximum impact to be possible. The key question that remains is whether the Treasury rules will go farther than other foreign legislation, given the predominance of many U.S. multinational companies in economies around the world. All will be revealed this week.