Movies to watch before confirming a Secretary of State

A few recommendations for Senators in their holiday free time.

Donald Trump has picked Exxon CEO Rex Tillerson to be his next Secretary of State. In a few weeks, US senators will either confirm or reject his nomination. What will they ask Mr. Tillerman?: Will he be a statesman or a deal-maker? Will he truly serve the poor and disenfranchised? Will he support citizens to hold governments and corporations to account?

At the risk of trivializing those questions, here are three movies I hope some Senators watch over the holidays.

Syriana (AKA: “Statesman or Dealmaker?”)

Syriana is an allegory from 2005 about the struggle between US short- and long-term national interests. US energy giant, Connex, is losing control over key Middle Eastern oil fields because Prince Nasir (Alexander Sidig), wants to reduce his countries’ dependence on oil, which he will get from a Chinese deal, but not from Connex. US long-term interests, brought to life by Bryan Woodman (Matt Damon), are to help Nasir succeed because over time the US will gain a stable trading partner in the Islamic world that is economically prosperous, more politically open, and doesn’t hate us.

What does the US do instead? It kills Nasir to lock in the short-term deal.

USAID was set up precisely because of this tension in US foreign policy. As President Kennedy said, “Money spent to meet crisis situations or short-term political objectives while helping to maintain national integrity and independence has rarely moved the recipient nation toward greater economic stability.” Effective foreign policy isn’t about short-term deal making, or zero sum competition. It is about fostering win-wins between nations, between the powerful and the disenfranchised, between the rich and poor. As the United States, when others win, you win too. Being CEO of Exxon in a world running out of fossil fuels is precisely the wrong training to achieve win-wins.

Mr. Tillerson may be a good deal-maker, overseeing revenues larger than Ukraine’s, and transacting in some of the most complex countries on the planet—think Angola, Yemen, Nigeria. But winning short-term deals is not the main purpose of US foreign policy. The Senate should ask Mr. Tillerson whether he plans to be a statesman or a deal-maker.

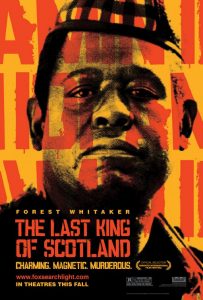

The Last King of Scotland (AKA: “Serving the Powerful or the Disenfranchised?”)

Idi Amin (Forest Whitaker) is likeable, until he isn’t. And our wiry Scottish hero, Nick Garrigan (James McEvoy) who goes to join a rural medical team, ends up becoming Amin’s doctor and finally realizing how badly Amin is damaging his country. The 2006 film unsentimentally contrasts the harshness of life for the poorest Ugandans with palace life for Uganda’s elites.

Why this movie? Because Mr. Tillerson may know parts of the world, he negotiated with characters like Amin and won good deals for Exxon, but does he really know what it is like to serve all people, the poor and the rich, the powerful and disenfranchised? As Secretary of State, he will sit over US global poverty fighting efforts and USAID. He will help lead America’s efforts to respond to humanitarian crises—USAID did that 60 times this year. He will be asked to make decisions that balance the needs of those who don’t have enough power against those who have too much.

This is the fundamental difference between life in the public and private sectors. As a public servant, your real bosses are the people you promised to serve. As a private businessman, Mr. Tillerson owes allegiance to his board and shareholders. The Senate should ask Mr. Tillerson how he will protect the interests of the poor and disenfranchised, so many of whom rely on the United States for sanctuary and support.

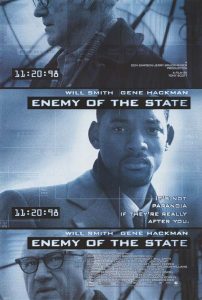

Enemy of the State (AKA: “Saving or Stifling Civic Life?”)

In Enemy of the State, NSA Official Tom Reynolds (Jon Voight), wants counter-terrorism legislation that will destroy the privacy of US citizens and civic life as we know it. Robert Dean (Will Smith) is America’s last hope, and doesn’t even know it. When “they” go after him, his only hope is Brill Lyle (Gene Hackman), who has somehow stayed disconnected and preserved his freedom to fight back. The 1998 movie is about the danger of secret power.

The danger of secret power is far from fiction in most countries where Mr. Tillerson has worked. I once heard the author Steve Coll say, “I’ve written books about the CIA, the Bin Laden family, and Exxon Mobil; and Exxon was by far the most secretive of the three organizations.” Oxfam knows all about Exxon’s secrecy. We’ve won victories in federal court these past years fighting the American Petroleum Institute (Tillerson was the Former Chair of API) to make US corporate oil and gas deals with developing countries far more transparent. Tackling poverty takes more than aid— transparency helps to ensure that the natural wealth of countries becomes national wealth for its citizens.

America at its most confident likes openness and self-criticism because in a meritocratic and open world, it does well. The US was founded on the principle that powerful institutions—corporations or governments—need citizens and civic life to correct their worst tendencies. Because it is more important to civic life than any other question, the Senate should ask Mr. Tillerson if he is willing to fight for open, transparent, and accountable governance overseas and to protect those who fight for justice.

The movie angle in this blog may not be serious, but the themes they evoke are deeply so. What do you think Senators should be thinking about as they prepare to confirm the next Secretary of State?