Turning the humanitarian system on its head

Oxfam has supported the Sudanese NGO SAG to hire internally displaced Darfuris to assemble fuel-efficient stoves for distribution to IDPs and other vulnerable communities in North Darfur. Photo: Elizabeth Stevens/Oxfam America

Oxfam has supported the Sudanese NGO SAG to hire internally displaced Darfuris to assemble fuel-efficient stoves for distribution to IDPs and other vulnerable communities in North Darfur. Photo: Elizabeth Stevens/Oxfam America

A new Oxfam report shines a spotlight on how since 2000 donors have met less than two-thirds of humanitarian needs in emergencies.

Shannon Scribner is the Humanitarian Policy Manager for Oxfam America.

In June of this year, the United Nations was appealing for funds to reach 78.9 million people across 37 countries. Today, the United Nations is responding to an unprecedented number of L3 or “mega crises” in Syria, Iraq, South Sudan, and Yemen. Recent news headlines such as “World Threatened by Dangerous and Unacceptable Levels of Risk from Disasters” and “U.N. Helpless as Crises Rage in 10 Critical Hot Spots” depict an overstretched humanitarian system. Simply put, while tens of millions of people are receiving vital humanitarian aid every year (Oxfam alone helped more than 8 million people in 2014), the humanitarian system can’t keep up.

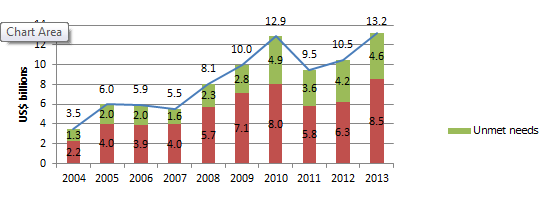

Today, Oxfam released a research report titled, Turning the Humanitarian System on its Head written by Oxfam’s brilliant researchers Tara Gingerich and Dr. Marc Cohen. The report is a nice complement to an Oxfam report written by Ed Cairns ahead of the World Humanitarian Summit titled For Human Dignity. Turning the Humanitarian System on its Head shines a spotlight on how since 2000 donors have met less than two-thirds of humanitarian needs in emergencies.

Aid shortfalls have led to devastating effects for people trying to survive in times of crises. In late 2014, the UN World Food Programme temporarily suspended food aid to 1.7 million Syrian refugees. And just this month, the UN had to again slash food aid to Syrian refugees due to funding shortfalls. Chronic underfunding occurs because UN member states do not make mandatory payments to any humanitarian fund or agency—unlike they do for UN peacekeeping missions. Even the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas imposes mandatory dues. The voluntary nature of humanitarian financing means that there are no predictable funding mechanisms for emergencies, so people in crises rely on the goodwill or in many cases political will of rich countries. As Jan Egeland, the former UN Emergency Response Coordinator has said, “Imagine if your local fire department had to petition the mayor for money to turn on the water every time a fire broke out.”

Funding and unmet needs, UN coordinated appeals, 2004-13:

Not only is there not enough funding, but when aid does arrive it is often too late and not always based on the most urgent needs. For example, the United States is the main donor to the World Food Programme, due to lobbying campaigns from agribusiness and the shipping industry that benefit from surplus crops being bought by the US government, which then pays American shipping companies to send food overseas. While food is a lifesaver, US food aid is not always the type of food people are used to eating, so they don’t always know how to prepare it, and it’s almost always cheaper to buy food locally or in the region of the crises. This reflects a larger problem of donors providing what they have on hand—boats, prefabricated shelters, ready-to-use therapeutic foods, or used clothing—rather than aid based on the most urgent needs.

Another issue the report points out is that not enough is being done to mitigate the impact of disasters. After the 2011 Horn of Africa drought, there was a lot of rhetoric from the United Nations, donors, national governments, and NGOs that more would be done to help countries build resilience to disasters. This makes sense because investing in reducing the risks to disasters saves lives and money. For example, long before this year’s earthquake in Nepal, the Nepal Red Cross estimated that for every $1 spent on disaster risk reduction (DRR) almost $4 would be saved in future disaster response. Yet, the promise to help countries build their resilience has not come to fruition. Over the last 30 years only 0.4 percent of total development assistance was spent on reducing the risks of disasters.

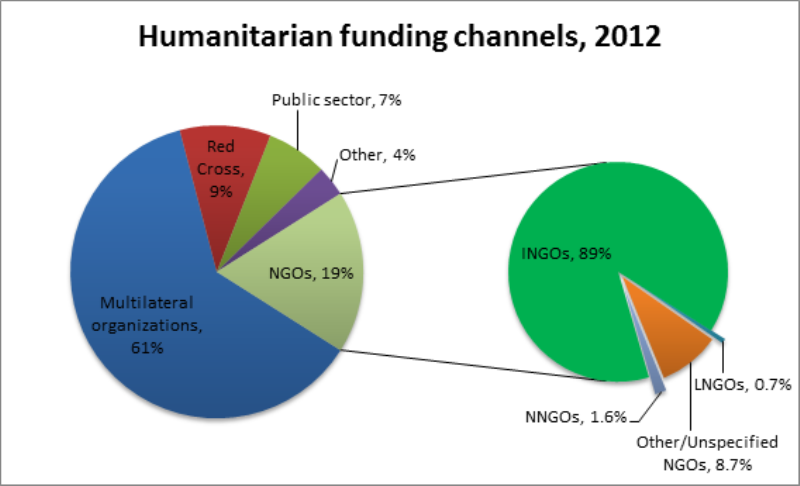

So, how do we “turn the system on its head?” Oxfam’s report calls for a shift of power and resources, including more direct funding to local actors (local NGOs, national NGOs, and national governments) with international actors (UN agencies, large international NGOs like Oxfam, and the Red Cross/Red Crescent movement) playing a greater role in strengthening the capacity of local actors to lead humanitarian action.

This doesn’t mean international actors step aside. The international community will remain critical to saving lives, especially in the aftermath of sudden-onset crises or where governments are unwilling to respond responsibly and equitably. This could be in conflict settings where governments are a party to the conflict or where aid is being delivered along lines of political affiliation and religion, as recently witnessed during floods in Malaysia.

But even in those instances, the international community should change its modus operandi. We should be looking first at existing capacity on the ground before taking the lead in humanitarian action or steamrolling over existing local capacity. And if leadership by internationals is necessary, we should devote resources to supporting and developing local capacity while we are responding.

The first place to start is getting more funding in the hands of local actors who are willing and able to respond. Oxfam research found that remarkably little humanitarian assistance goes directly to national and local NGOs in crisis-affected countries. In 2012, only 2.3 percent of humanitarian funding went to them directly while nearly 98 percent went directly to international NGOs and the Red Cross. And this is a trend.

From 2007-2013 only 1.87 percent of humanitarian assistance went directly to local actors, such as members of the Humanitarian Response Consortium in the Philippines that were perfectly capable of responding to the country’s recent typhoons.

Locals are the first responders when crisis hits, know the local context better than internationals, often have better access and remain long after the cameras and international community have left. In response to Typhoon Haiyan, one of Oxfam’s local partners said:

“I was attending a UN meeting and heard that the area we were working in was considered hard-to-reach. But it’s on the main road and we travel there every day. Perhaps it’s hard-to-reach by international, rather than national, standards…”

Moreover, when international NGOs do provide direct funding to local actors, they frequently treat them not as true partners but as sub-contractors who are carrying out plans designed by the international actors with little ownership from local actors.So what can be done? We must strive for a system that responds from the bottom up, where national governments exercise their responsibility to protect and assist their own people and citizens are supported to respond and hold their governments to account. We need to start with:

- Predictable humanitarian funding. One idea is to have mandatory assessed contributions to humanitarian emergencies. This would be similar to mandatory assessments for UN peacekeeping missions charged to member states.

- More humanitarian funding to local actors. Oxfam is calling for at least 10 percent of global humanitarian funding to go directly to local actors by 2020.

- Increased investment in disaster-risk reduction before crises hit. Oxfam is calling for an increase of $5 billion in annual overseas development assistance for disaster-risk reduction.

- A commitment by international actors to do more to strengthen local capacity. This includes strengthening technical (water and sanitation, shelter, and humanitarian principles and standards) and organizational (financial and human resources systems) capacity.

We know that the international humanitarian system created decades ago has saved thousands and thousands of lives. And we know that international and local humanitarian aid workers have worked against enormous and increasing challenges, with relatively few resources to save lives. Yet, we also know that the humanitarian system is overwhelmed and underfunded at a time when natural hazards are projected to increase in both frequency and severity.

Knowing all of this, shouldn’t we try to do better by creating more predictable funding and a humanitarian system that is more bottom up with national governments at the center, supported and held to account by their own civil societies? Oxfam is endeavoring to work increasingly with local and national NGO partners and governments to strengthen the quality of our partnerships while strengthening partners’ capacity. Oxfam is ready. And we call on other international actors to join us.