How to keep score when donors make promises

Last November, in Busan, Korea, donors reaffirmed their past promises to make their aid more useful to people developing countries. They also agreed to measure themselves so the world could track how well they were implementing these promises. But the debate over *how* they are willing to be measured is still raging—and won’t be decided […]

Last November, in Busan, Korea, donors reaffirmed their past promises to make their aid more useful to people developing countries. They also agreed to measure themselves so the world could track how well they were implementing these promises. But the debate over *how* they are willing to be measured is still raging—and won’t be decided until June. At the World Bank on Friday, Oxfam will be hosting an event to talk about progress towards implementing the Busan Partnership. New research by Oxfam and others provides new data as to how important keeping score is for driving political change—as well as suggesting how to best measure the promises made at Busan.

Bureaucracies are hard to move; they seldom ever move when bureaucrats feel comfortable. So, one of the key components of forcing political change is being able to make policymakers uncomfortable enough with the status quo that they make hard changes.

One thing that gets policymakers’ attention is being compared to one another. A government that is shown to be falling behind its peers can be shamed into making changes to catch up. But that shaming requires good, comparable data that governments cannot hide from. Naturally, governments are often reluctant to endorse effective scorecards because it shines a light on their behavior.

This new research affirms that keeping score on implementation of the Paris Declaration helped push implementation of Paris principles. Signatories to Paris instituted a global monitoring framework to measure and account for how well governments were living up to their promises. A review of donor peer reviews conducted by the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee indicates that the global monitoring system was a success in incentivizing policy changes in donor capitals.

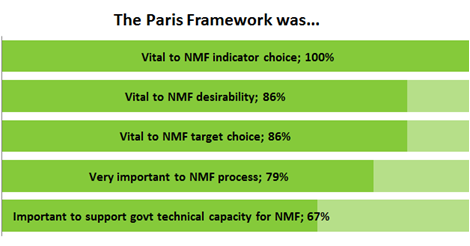

The Busan Outcome Document emphasizes that the focus of work to make aid more effective should be “global-light, country heavy”; in other words, the emphasis should be on progress made at the country level. And development progress indeed happens at the country level. Nonetheless, accountability for such progress requires comparing the progress of different countries against one another. In fact, the research shows that Global Monitoring is a huge guiding factor in determining the strength of national results frameworks. To quote one partner country respondent, “The Paris framework was crucial to getting donors to agree that they should be monitored.”

Of partner countries who are successfully implementing National Monitoring Frameworks (NMFs):

Some research respondents went so far as to argue that the biggest constraint to a national framework was the lack of political commitment on the part of their donor partners. In fact, some respondents said most donors were not willing to increase their national level obligations beyond what Paris called for.

So from this evidence, what conclusions can we draw about what the Busan monitoring system look like? Here are some thoughts:

• You need globally comparable indicators to drive country level change. A key feature of the Paris monitoring framework was the ability to hold stakeholders accountable by comparing them with their peers.

• The framework needs to monitor all major Paris, Accra, and Busan commitments, in line with the Busan Partnership Declaration. Rule #1 of development strategy is, “what’s measured is meaningful.” If any particular commitment is left out of the final monitoring framework, it will inevitably be deprioritized by stakeholders.

•Civil society stakeholders should be included in the design, implementation and accountability of the global monitoring framework through a transparent and representative process. If civil society isn’t actively engaged and does not have the space to hold their government accountable, the monitoring framework won’t push those changes that poor people most need.

•The new monitoring framework must integrate cross-cutting gender equality and women’s empowerment targets in all commitments measured, as stated in the Busan Partnership Declaration. Again, without measuring against these criteria, gender issues could be neglected.