The data revolution will not be televised

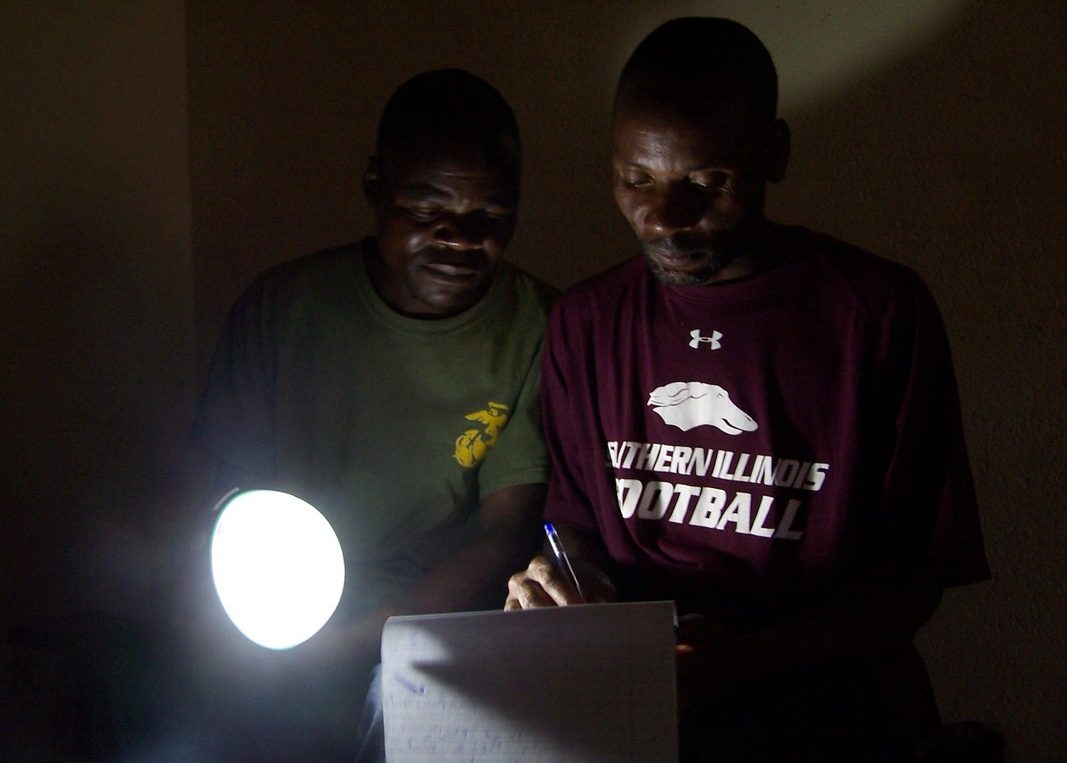

Villagers examine the production data showing the different phases and output levels and crops grown in the Ruti irrigation scheme. Zimbabwe - Rural Sustainable Energy Development Programme (RuSED).

(Photo: John Magrath / Oxfam)

Villagers examine the production data showing the different phases and output levels and crops grown in the Ruti irrigation scheme. Zimbabwe - Rural Sustainable Energy Development Programme (RuSED).

(Photo: John Magrath / Oxfam)

Why transparency matters for development.

Last week President Obama signed into law the Foreign Assistance Transparency and Accountability Act of 2015. Oxfam supported this bill, saddled with the not-so-catchy moniker “FATAA,” since it was first introduced in 2012. Success at long last has come from bipartisan leadership in both the House and Senate, under the recognition that smart development policy is in the national interest. We’re glad to see their efforts come to fruition, and the Obama administration’s gains and commitments to aid transparency institutionalized.

FATAA requires US aid agencies to evaluate their programs and publicize the results, and to keep publishing data on aid investments in line with the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). More and more actors are now publishing data under IATI, and IATI as an organization is now looking at how to promote use of the data, recognizing that expanding use is critical to sustaining the initiative.

But bipartisan wins in Washington and international aid policy meetings in Copenhagen aside, how will more transparency in development ultimately benefit people in partner countries?

Put another way, the sustainability of IATI is not the point.

I would even say that promoting more use of aid data isn’t the point. As the critical role of open governance, transparency and accountability has become conventional wisdom in development, the point of aid transparency is to transform the aid system: to shift power to citizens, and accelerate the move towards genuine partnership.

The aid world has rebranded “aid” as “development cooperation,” and the final Sustainable Development Goal, Goal 17, aims to “revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development” A steely-eyed James Bond appears on the Global Goals page for Goal 17, underscoring that this is serious business.

But if we are serious about being better partners, we need to show it with our actions. Donors need to do more than publish data. They need to publish data that puts aid on budget, so governments can plan and the people’s representatives in parliaments and civil society can hold governments and donors to account in the context that is politically salient to them–the country’s own finances.

Donors and implementers need to put out better data on results, and support capacity to use it, so partners can manage for impact and allocate resources to projects that work.

Fundamentally, the aid development cooperation system needs to open up opportunities for people to use data to influence decisions about development priorities and how best to address them, so people in “partner countries” can actually be partners, not “beneficiaries.”

Better data on aid should be a development asset in its own right–a tool that local actors can use to make their own work to fight poverty and injustice more effective. The data must be useful for the inherently political work of building more open and inclusive governance.

That means we need to talk to the people doing this vital work at the local level, and understand what data they actually need. Then we need to deliver the data that puts more power in the hands of the people on the front lines of development.

US Ambassador to the UN Samantha Power described this move towards authentic partnership as a “revolution for dignity” at the White House today.

That’s a data revolution we can get behind.