This year, the Best States to Work Index charts a new way that states are actively moving BACKWARD: by weakening restrictions on child labor. That’s right: child labor.

Industrial laundries. Freezers and meat coolers. Roofing. These are some of the most hazardous workplaces in the country, featuring extreme heat and cold, heavy machinery, slippery surfaces, heights. They pose dangers to the most seasoned and careful workers.

These are not places where children (under 18)* should be working; and yet some states are starting to dismantle their protections for children at work, weakening laws around sectors, hours, and tasks.

And the consequences will be deadly. Just this summer, three teenagers died in accidents at a poultry plant in Mississippi, a sawmill in Wisconsin, and a landfill in Missouri.

The likelihood of children dying in dangerous jobs did not deter states from rolling back restrictions on child labor in the past two years. Iowa passed a law allowing 14- and 15-year-olds to work up to six hours a day when schools are in session, to as late as 9 p.m. (during school vacations, as late as 11 p.m.); it also removes prohibitions against minors working in industrial laundries, demolition, and in freezers and meat coolers. Arkansas eliminated work permits for 14- and 15-year-olds. New Jersey and New Hampshire extended work hours. Several other states are considering making similar changes.

We added this (terrible) data point to this year’s Best State to Work Index (BSWI) in order to train a spotlight on new efforts to undermine labor standards, enlarge the low-wage workforce, and take advantage of working families.

The growing gaps between best and worst states

Why is there such wild disparity between states laws? Credit Congress, which has been deadlocked in partisan divides for years now. The most glaring example? The federal minimum wage has not been increased in 14 years, the tipped minimum wage in 32 years; while 30 states have increased their state minimum wages, 22 have not, leaving a dangerously low wage floor of $7.25 an hour ($2.13 tipped).

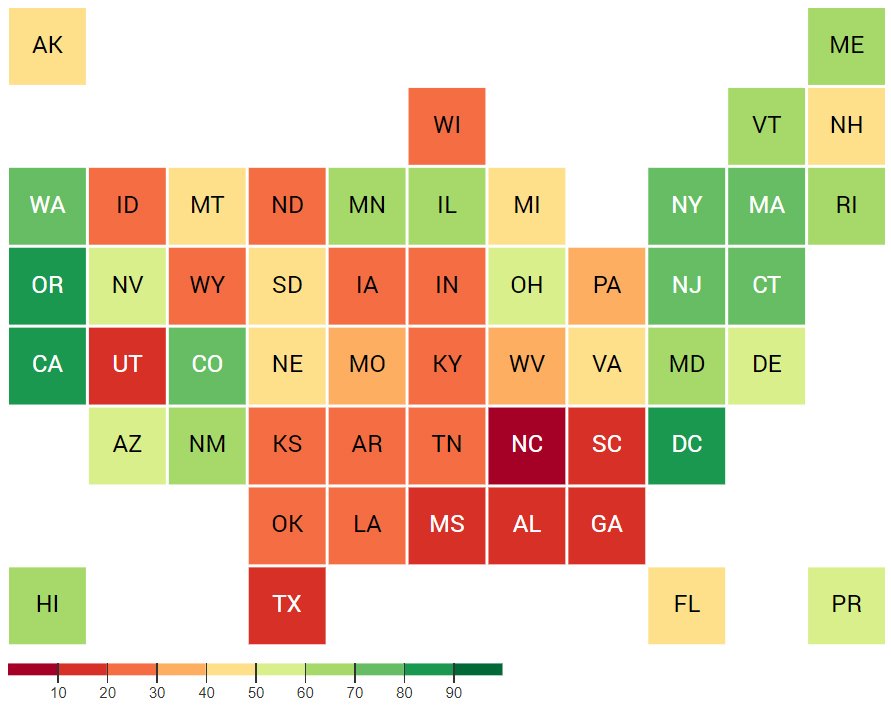

Clearly, geography is an important dimension of systemic inequality in the U.S. State boundaries draw lines around fundamental rights, conditions, and protections for citizens, and within those boundaries are very different realities.

When Oxfam published the first edition of the BSWI in 2018, we were surprised to see the wide range of labor laws across the country. At that point, the top and bottom states sat right next to each other: Washington, DC was #1, and Virginia was #51. The minimum wage alone was almost double in DC what it was in Virginia ($13.25 vs $7.25 then; happily $17 and $12 today), and protections and rights to organize were similarly diverse.

Now, in 2023, the disparities are still there—but they’ve gotten even deeper. The top states continue to make progressive changes to labor laws to help working families stay afloat and healthy, while the bottom states remain obdurate, refusing to take simple steps like raising the minimum wage.

A few states have taken action with important new laws; this has improved the landscape for working families—and bumped them up in the index. We’re delighted to see changes in Virginia (from #51 to #28), Colorado (from #15 to #8), and New York (from #11 to #4). (Please read more about the historic retrospective in the full report.)

It needs to be said that the best states are getting better because of a circle of virtue: where workers and advocates are empowered to organize and demand changes, state legislatures respond (in the best states); where workers are underpaid and ignored, legislatures for the most part refuse to act.

The gaps between the best and worst states are huge, and meaningful

If you live and work in one of the best states, you’re doing better on all three dimensions of the BSWI. You make dramatically better wages (even accounting for cost of living), have much more robust protections at work, and have rights to organize and bargain collectively.

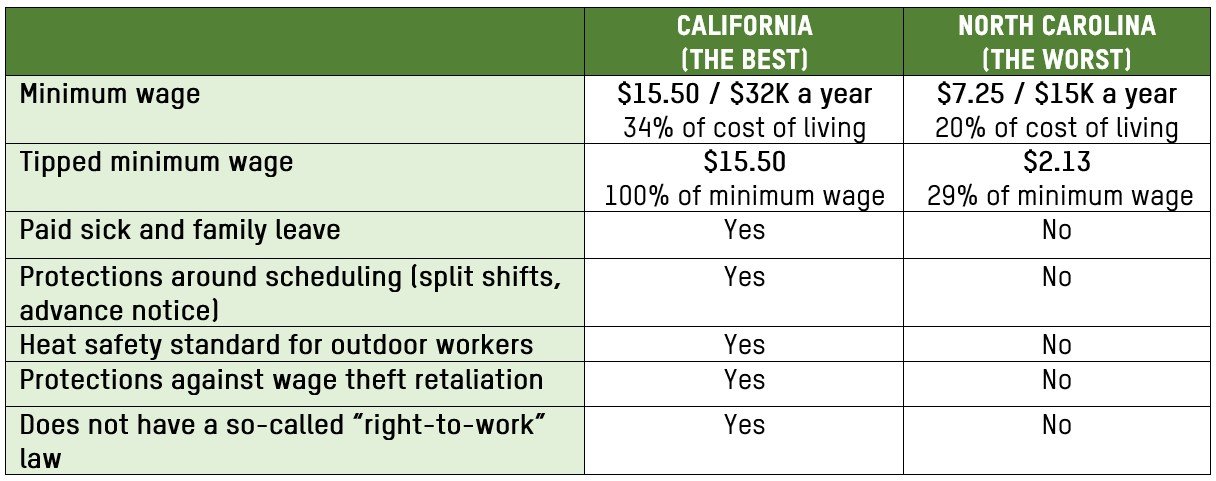

The table below captures some of the data points in the top state (California) vs the bottom state (North Carolina).

These are not just policies and data points; they are living laws that help determine a family’s income, conditions in the workplace, and rights to unionize.

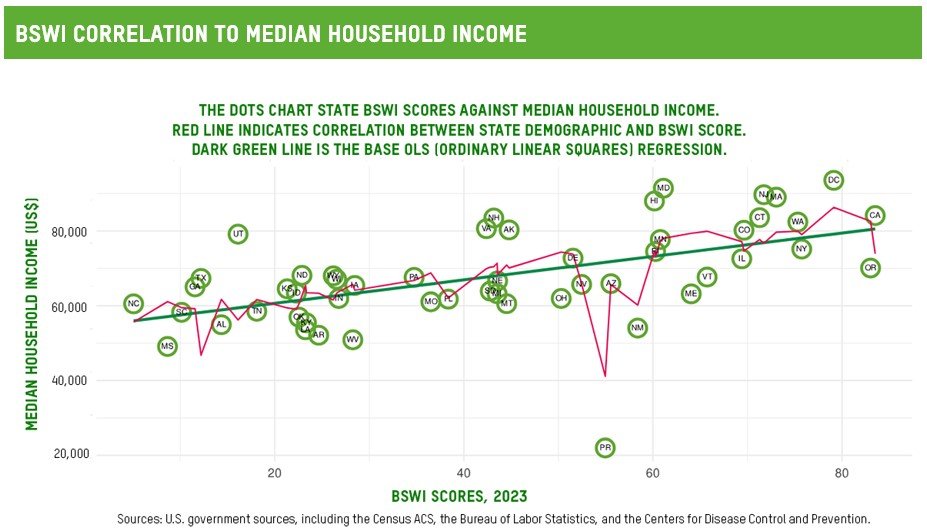

This year’s report offers data on how scores on BSWI correlate with important measures of well-being in each state. The charts are simultaneously shocking and not surprising: States that score well on the BSWI are also states where people earn higher incomes; experience less poverty, food insecurity, and infant deaths; and have higher rates of unionization—and the disparities are huge.

The overwhelming need is for Congress to establish federal standards that support working families in every state. As long as Congress fails to act, working families in the worse states will, unfairly, face terrible odds as they try to stay afloat and get ahead. (Please read more about the advocacy agenda in the issue brief.)

What can Congress do?

We need federal standards that protect ALL workers, no matter where they live. Briefly, Congress should:

- Raise wages: The federal minimum wage has not been raised from $7.25 an hour since 2009. Both at the state and the federal levels, Oxfam calls on policymakers to abolish tipped wages, end minimum wage exclusions of certain workers, and lift the minimum wage. The Raise the Wage Act would accomplish all this at the federal level.

- Strengthen worker protections: There is a great need for stronger worker protections at the state and federal levels, including paid family and medical leave, stronger equal pay laws, and protections for domestic workers. There are several bills before Congress [ES1] that establish federal paid leave standards, including the FAMILY Act and the Healthy Families Act. The Domestic Workers Bill of Rights Act extends pay and leave rights to domestic workers while mandating health and safety precautions, and it includes language around fair and fixed scheduling.

- Protect rights to organize: The federal government must protect the rights of workers to build power collectively. At the state level, the prevalence of “right-to-work” laws demonstrates the systematic approach to undermining worker power; the federal government has one crucial piece of legislation to pass: Richard L. Trumka Protecting the Right to Organize Act (‘PRO’) Act.

Take action to urge Congress to prioritize the needs of all working families across the country.

_________________________

* Oxfam and the federal government regard anyone under the age of 18 as a child.

Explore the interactive map to see how states compare

See the 2023 map for all workers

See the 2023 map of Best States for Working Women

Check out the full history of the BSWI: Previous editions

- See the 2022 map for all workers

- See the 2021 map

- See the 2021 map of Best States for Working Women

- See the 2020 special edition: Best and Worst States to Work in America – During COVID-19

- 2020 regular edition

- 2019 edition

- 2018 edition