Resilience in my neighborhood and beyond

This is the second in a series of blogs considering the options for and barriers to agricultural resiliency. Years ago I heard a banker say that if he had to choose between managing an agricultural loan portfolio made up of 20 mid-sized farms covering 10,000 acres or five large farms managing the same area, he would […]

As I see it, the banker was saying that one system was more resilient, even though in terms of the economies of scale, the consolidated model might have had some advantages. But in the interest of social and economic stability, having more people and farms provided a better hedge against collapse.

With an expanding global population, communities and nations must face the question of which model suits their needs as erratic weather, volatile markets, finite arable land and fresh water tightens the vice on the global food system. Now that extreme heat and drought are sweeping across my own farm and across more than 1,000 counties in 26 states, I’ve considered some of the things that my neighbors do to buffer the impacts of both environmental and economic shocks.

First, two miles to the south, Roman and Ruth Miller used to only grow wheat, row crops, and cattle. About 15 years ago, they took about a quarter of an acre out of conventional crop production, and started a modest market garden. Since that time, the vegetable production has expanded; they built several hoop houses to extend the growing season; and with the assistance of their children, the Millers became more and more adept at marketing. Roman still has wheat and cattle, but he has created a side enterprise that has allowed him to become more profitable and economically secure without having to buy more land or invest in more expensive machinery. (The role of entrepreneurship and farm diversification is covered well in work by Cornelia and Jan Flora , and Karl Stauber)

Next, I think about my friend, Gene Albers, who farms about 30 miles from my operation. Gene incorporates cover crops into his diversified crop and livestock operation. He believes that conserving soil is not enough. A farmer should improve the soil through building up organic matter and biological activity. By planting mixes that might contain seeds of turnips, Japanese radishes, black oats, barley, pearl millet, and Austrian peas, Gene can create ground covers that shade the soil, penetrate compacted soil, and capture nitrogen. By grazing livestock on crop residues and cover crops, Gene has been able to capture more value while effectively recycling nutrients.

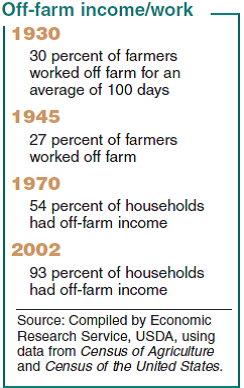

Finally, I think about my brother-in-law, Jamie Funke. Jamie married the daughter of a farmer who taught vocational agriculture at the local high school. Jamie also has a career in education working at the area community college. He farms 320 acres of wheat, soybeans, and grain sorghum in his spare time. Like the majority of his neighbors and the majority of American farmers, having an off-farm job allows Jamie to remain a productive farmer with access to affordable insurance, and a steady source of cash flow.

Three farms. Three strategies for stability, resilience, and success. The Millers have concentrated on agricultural enterprise diversification and entrepreneurship; Albers focuses on building the health and productivity of the soil; Funke has found that off-farm employment can better ensure his continued engaging in farming.

Right now, we are all in our second year of severe drought – a situation similar to the one plaguing rural people in the Sahel, and regions in the Horn of Africa. The ramifications of the drought are different – people in Africa face food emergencies and possible famine. However, my neighborhood examples provide some element of what investing in resilience might look like regardless of location.

Facing the challenges of increased flooding, longer lasting droughts, and volatile markets may mean that the monoculture, mega-farm will not be the best target for emerging agriculture in the developing world. What may be the more stable, and resilient models could depend more upon investing in smaller operations that enable entrepreneurship, off-farm income generation, and agro-ecological strategies, which build soil and conserve water.