Resolving company-community conflicts: What’s the role of corporate leverage?

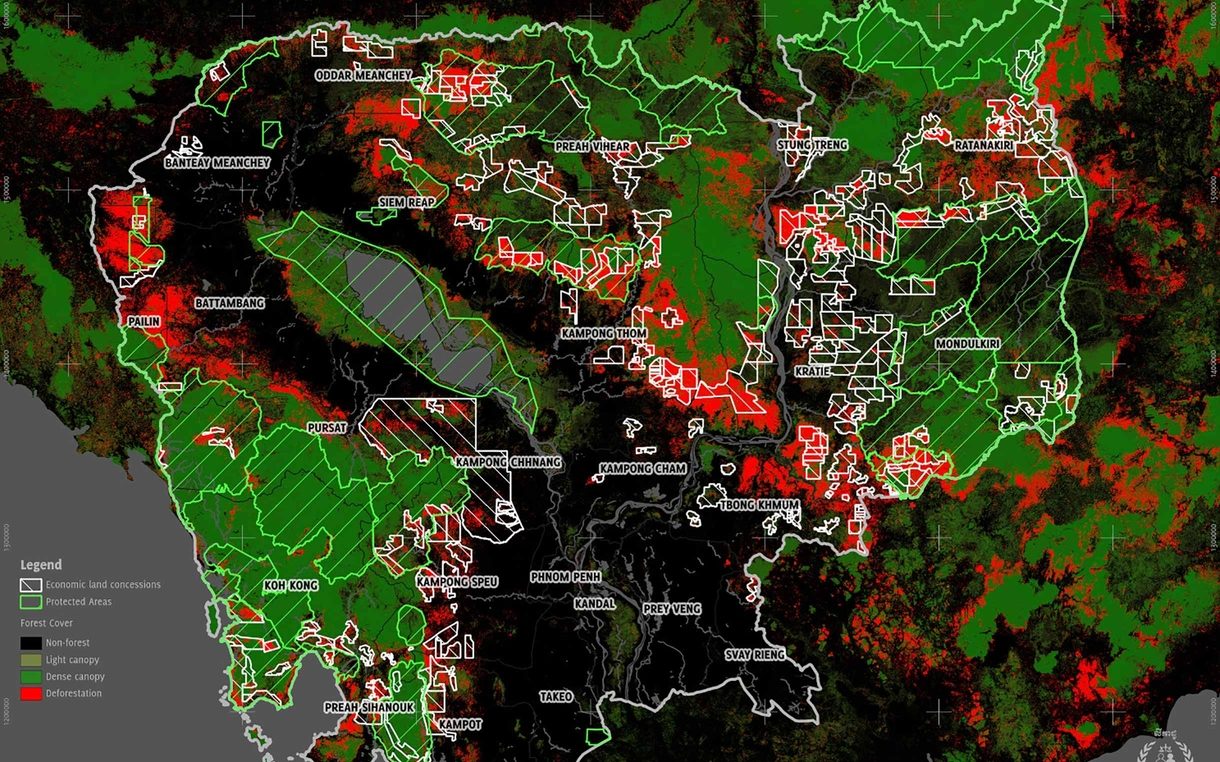

This map, created by the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights, shows land concessions (white lines) and areas of deforestation (red) in Cambodia. Mitr Phol’s concessions were in Oddar Meanchey, which is in the northwest part of the country.

This map, created by the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights, shows land concessions (white lines) and areas of deforestation (red) in Cambodia. Mitr Phol’s concessions were in Oddar Meanchey, which is in the northwest part of the country.

Multinational companies have a responsibility to use their leverage to help resolve conflicts that arise with communities affected by their work. To do this, recent thinking suggests they’ll need to change more than just corporate practice.

My colleagues recently wrote a blog post about the role of palm oil companies and their buyers in a deadly ecological disaster in Guatemala. In it they explain how Cargill and Wilmar – international buyers of palm oil from the Guatemalan company in question, Reforestadora de Palma del Petén SA (REPSA) – should use their ‘leverage’ to encourage REPSA to remediate harms to and respect the human rights of community members affected by its operations.

Merrick Hoben from the Consensus Building Institute (CBI) also recently published a blog post about his work on this conflict. He posits that “sometimes designing a legitimate dispute resolution process requires examining both company responsibilities as well as deeper structural problems.” (He also offers an insightful list of six ingredients critical to a successful resolution process relevant in Guatemala and other contexts, which he elaborated on in an Oxfam-hosted panel at the World Bank Land and Poverty Conference in March).

My key takeaway: Cargill, Wilmar, and other companies must use their leverage to ensure REPSA participates in a legitimate resolution process, their first responsibility. But to ensure meaningful resolution of complex company-community conflicts such as this, both buyers and suppliers, REPSA, Cargill, Wilmar, and others, also need to use their leverage with government officials and other stakeholders to tackle broader, systemic issues at the root of the conflict. This is true in Guatemala and other contexts.

What is leverage?

Leverage is a core concept in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. The organization Shift defines leverage as simply “a company’s ability to influence the behaivor of others.” Companies can exercise leverage over suppliers by making future contracting contingent on the supplier reaching certain human rights milestones, offering incentives for change such as long-term business, and building capacity of the supplier to address the issues. They can also use their leverage with other stakeholders to help enable respect for human rights, including: governments, when government regulations or practices stymie efforts; industry associations, when their regressive lobbying undermines progress; and peer companies, when resolution will require multiple companies working together.

Human rights violations related to land rights and land use are among the most visceral and complicated issues for companies to address in their supply chains. When a company or government takes away people’s land or pollutes communities’ water sources, they’ve taken away their source of food, water, and livelihoods, their homes, and links to their cultures and traditional ways of life. Women often experience the worst of these effects. Investments often divide communities too, causing rifts in social structures. These conflicts are usually prevalent where governance systems are weak, judicial systems untrustworthy, and corruption rampant.

Resolution is complicated. In these contexts, a lasting solution requires corporate change, but more than that too.

Consider a different land conflict in another complex environment: Cambodia. This case involves Mitr Phol, a Thai company with supply chain links to Coca-Cola and other multinational companies. Read background on the case here. Mitr Phol returned its land concession areas to the government of Cambodia in 2014, citing the conflict as one of its reasons for withdrawl. Despite Mitr Phol returning the concessions, communities have yet to receive compensation for harms and losses. Coca-Cola and private sector actors must continue to use their leverage to ensure Mitr Phol provides the remedy that communities seek. This is an urgent priority and first responsibility.Yet the sad truth is that even after these communities receive compensation, they’ll still face risk of losing their land to another investor in the future.

In Cambodia and elsewhere, corruption, insecure land rights, and gaps in governance systems and regulations create an enabling environment for land grabs and company-community conflicts. In addition to focusing on community compensation, it’s important to consider how the companies involved – Mitr Phol included – could also use their leverage to help tackle the underlying issues at play. Companies are powerful actors in these contexts. Often part of the problem they have a responsibility to be part of the solution.

But successful exercise of company leverage to inspire change in company operations and address systemic issues is not something we see often enough, especially when it comes to issues of land rights and land use. It’s an area of work that demands more attention.

Do you have examples from your work where you’ve seen companies exercise their leverage over suppliers, governments, peer companies, and others to help resolve land or land-use conflicts? We’d be curious to hear about it.