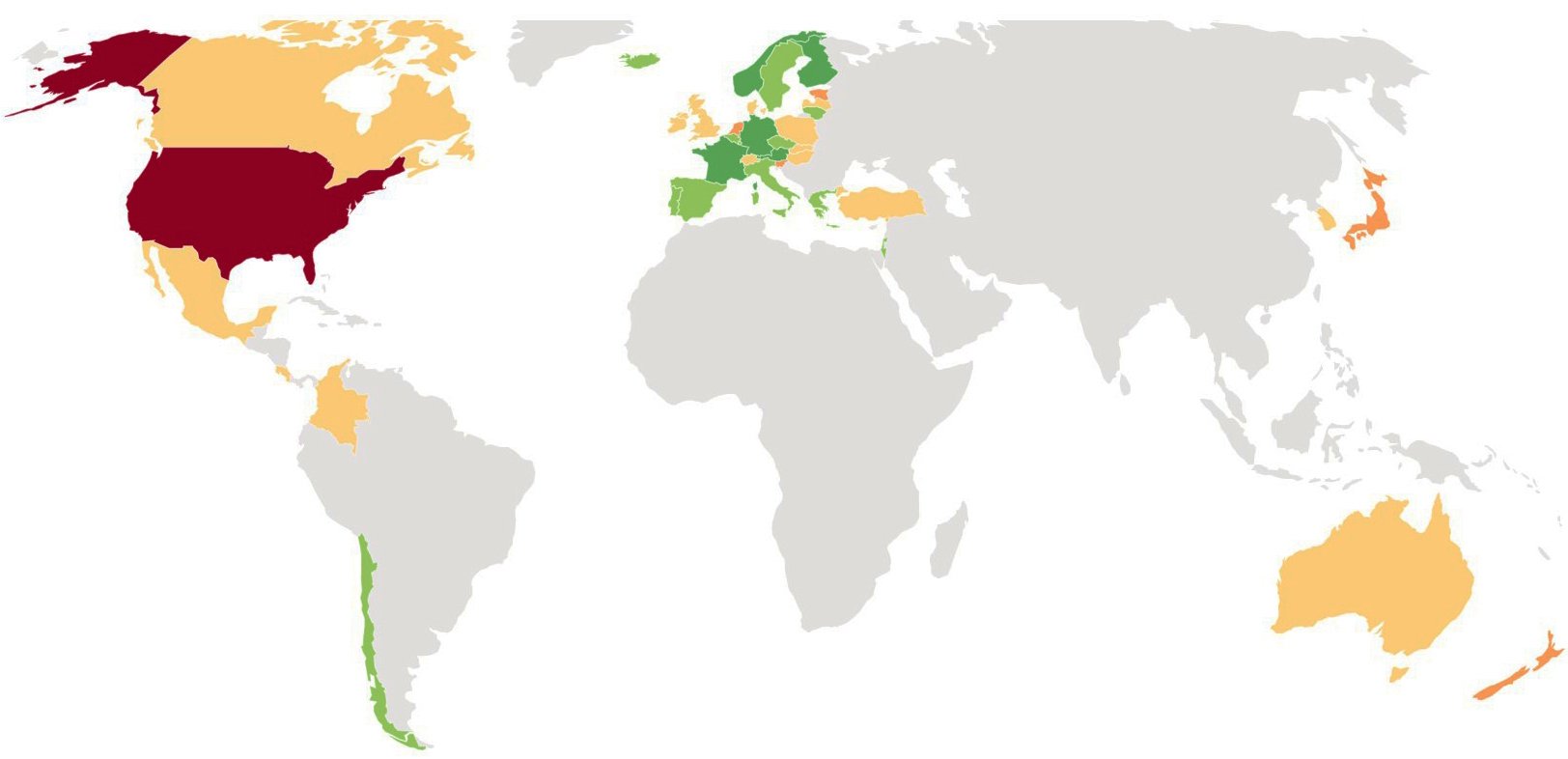

Oxfam’s new index of labor laws among peer nations shows you can have a robust economy AND a thriving labor force. Why is the US such an egregious outlier in failing to support working families? Look to race, class, and gender… And inequality.

A while ago, researchers at Oxfam set out to answer a question: if we compare labor laws in the US to peer nations, how does the US stack up? We figured the answer would be “not so great.” We didn’t anticipate just how poorly the US is doing.

It turns out that the US is at or near the bottom of every dimension of labor laws. Wages. Worker protections. Rights to organize. As the newly released Where Hard Work Doesn’t Pay Off index lays out, the US fails to mandate measures that would guarantee a decent living, safe conditions, and freedom of association.

Indeed, our country does little to mandate respect for the dignity and humanity of all workers and their families; we leave it to employers to decide if they want to accommodate the very real needs of their workers. And they very often do not.

In stark contrast, our peers do vastly better in making sure the economy supports ALL workers and working families. Specifically, nearly all the other 37 nations in the new index have more robust labor laws (we measured the US against members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or OECD, as these countries all have relatively robust GDPs, and commit to democracy and free markets).

Here’s the what, then we’ll explore the why.

This is just a snapshot. The full index includes 56 data points and offers a sophisticated analysis of labor laws. Please explore the interactive map, the report, and the full data in the spreadsheet.

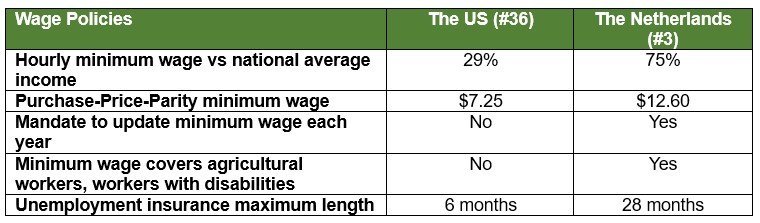

Wages: The US ranks #36 (out of 38)

The US has not raised the federal minimum wage in 14 years, leaving millions of working families living in or near poverty, no matter how hard they work. Other countries—from the wealthy to the middle-income—do much better in raising the wage floor and mandating better wage supports.

For example, let’s compare the US to the Netherlands on a few data points.

Worker protections: The US is dead last in this dimension

Other economic peer nations have passed a variety of laws that support workers as full humans with complex lives. Measures include numerous forms of paid leave (for new parents, for problematic menstrual periods, for illness and family obligations, and more); robust child care supports; healthcare; and much more.

How does the US compare to the top-ranked country, Germany? Just a few data points:

Rights to organize: The US ties for #32 in this dimension

Labor unions provide consistent, significant benefits to workers and their families; as the degree of unionization has declined in the US, workers have experienced decreases in prosperity and power. In recent decades in the US, rights to organize have been eroded and attacked by some branches of government and by private corporations.

Other countries in our index do much more to protect rights to organize and bargain collectively; unionization rates are much higher, and, not coincidentally, labor laws are much stronger.

Why is the US such a laggard in labor laws supporting working people?

The US has a tragic and unique labor history. It exploited enslaved labor in cotton gins and mills, sawmills, sugar refineries, railroads, and more. It relied on immigrant labor to build railroads and power the industrial revolution; to this day, it exploits immigrant labor in agriculture, meat and poultry processing, fishing, domestic care, building maintenance, restaurants and hospitality, and more.

In general, employers did and do take advantage of the precarity of workers in these situations. They paid them less, exposed them to more dangerous and arduous conditions, and stifled any attempts to organize or bargain collectively. And for decades, the law did little or nothing to protect workers and working families.

Finally, the federal government stepped up to develop and enact the New Deal (under the leadership of FDR, in the midst of the Great Depression), which included, among many other measures, union protections, Social Security, and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which established the federal minimum wage, overtime pay, rights to organize, and more.

However, due to pressure from Southern lawmakers, the labor standards law did NOT (and does not) extend to industries that employ primarily Black and immigrant workers: agriculture, restaurant service, and domestic care. Workers in these sectors remain unprotected by federal labor laws (with some exceptions: see Oxfam’s Best State to Work Index).

Bottom line: we still have a stratified labor market in which millions of people are caught in low-paying, dangerous jobs, and employers are allowed to exploit them.

In short, our economy regards some people as less valuable, and who therefore deserve less: less dignity, fewer protections, fewer rights. They do the most difficult jobs AND have the lowest wages, fewest protections, and scant rights to organize and bargain collectively.

The result? A permanent underclass of working people trapped in cyclical poverty.

This, at the same time that we have a thriving economic engine that delivers prosperity and enormous wealth to some of us, from billionaires to the middle class. The truth is that MANY enjoy the fruits of our enormous and robust economy: we get paid decent wages, enjoy benefits like paid vacation and maternity leave, and have the freedom to organize and speak out.

But millions of people are denied these rights—and they are very disproportionately BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color), immigrants and refugees, and women. Oxfam research found a dramatic concentration of demographics in jobs paying less than $15 an hour: While 25 percent of working men earn less than $15, 40 percent of working women do; HALF of working women of color earn less than $15. In 25 states, at least 60 percent of working women of color earn less than $15.

And these are the workers who are denied protections and rights. We have chosen to allow employers to decide whether or not they WANT to award the “privilege” of paid sick and maternity leave to workers. And the result is that they choose to give it only to some—usually the wealthier and more privileged. For just one example: of earners in the top 10%, 96% have employer-provided paid sick leave; of earners in the bottom 10%, 38% have paid sick leave. Over half of low-wage workers are living without the safety net of paid sick leave.

Naturally, those who can’t afford to miss a day’s wages are those earning the least; countless working families are struggling to care for households while working through illnesses and crises, because they have no accommodation to take care of themselves and each other.

This does not happen in most of our peer nations, where federal protections and mandates extend to ALL workers, in every industry. Any worker who gives birth in ANY of the countries measured in the index enjoys paid maternity leave—from six weeks (in Portugal, though most are closer to three months) to 43 weeks (in Greece). Any worker who falls ill in any of the other countries enjoys paid sick leave.

Without sufficient Congressional action on labor laws, this leads to not just stasis, but an actual exacerbation of inequality for workers. Low-wage earners are losing ground as wages stagnate and decline; when they work without healthcare, they are ending up with staggering medical debt; when a deadly pandemic sweeps the world and they have no paid sick leave, they are enduring exposure and illness.

This reality is unnecessary. It harms workers and their families and erodes our democracy and prosperity. Other nations manage to have robust, thriving economies while also treating all workers as full people, with full lives and dignity. Workers are more than their jobs. They have households and families, take care of children and parents and the disabled, and deserve paid leave and accommodations for real-life developments like pregnancy, illness, and emergencies.

The US can and must do better for ALL workers.

_________________

Oxfam has developed a robust policy agenda for labor laws in the US. Please refer to this issue brief.